About Publications Library Archives

cthl.org

Preserving American Heritage & History

Preserving American Heritage & History

This article was initially published during the impeachment trials of President Donald J. Trump, whom was acquitted of two charges of impeachment.

Americans have long celebrated the February birthdays of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln—Washington on February 22, 1732 and Lincoln on February 12, 1809. Washington’s Birthday became a federal holiday in 1885. But in 1971, the third Monday in February replaced Washington’s Birthday by becoming Presidents’ Day. This created a national holiday, giving workers a nice three-day weekend. But for many, this diminished the grandeur of Washington and Lincoln, America’s greatest Commanders-in-Chief, by homogenizing their honor with less stellar American chief executives.

While the holiday still evokes the memories of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, according to polls of younger Americans, Bill Clinton is prominent and is even considered one of the great US presidents. However, this year’s celebration of America’s presidents highlights the name of Clinton for another reason—impeachment. He is among that unenviable circle associated with the dubious honor of presidential impeachment composed of Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon and now Donald Trump.

It may be jarring to read the concatenated words—Washington, Presidents’ Day and Impeachment—but there is a connection between them. Washington was the presiding officer at the Constitutional Convention that established impeachment as the manner of removing high officials from public office. As the first president, celebrated before there was a Presidents’ Day, his character set the standard for all other presidents whether they served with honor or faced legitimately or illegitimately the dishonor of impeachment.

Just what does impeachment mean anyway? A look at its etymology—how the word developed in history—helps us to understand what it implies. The word comes into English from Old French and Latin words that express the idea of catching or ensnaring someone by the foot. In Late Latin impedicare meant to catch or to entangle, derived from the word pedica meaning a fetter. A fetter was placed on the foot of a detained person least he escapes. If caught by the foot, one is prevented from moving forward. The word appears in late Middle English where its sense was to hinder, or to prevent. This led to our English words impede and impeach that have similar meaning.

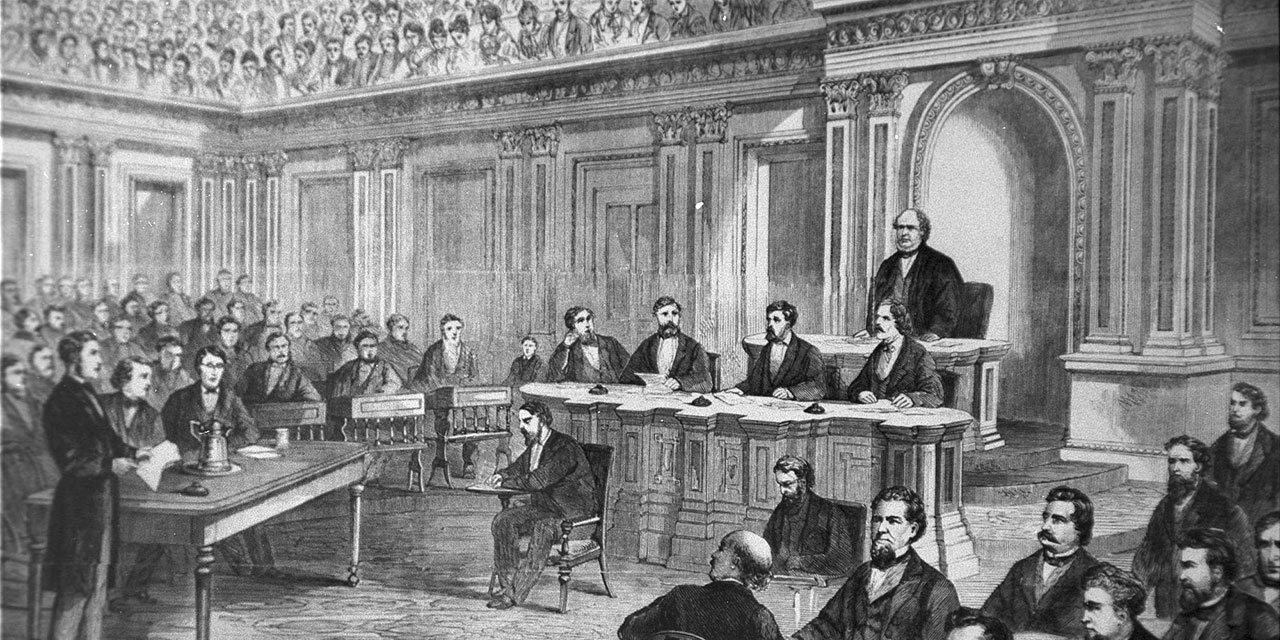

Contemporary synonyms show that the meaning of impeachment has expanded from hindering to a more legal sense: accuse, charge, defame, incriminate, indict. Impeachment, then, is the impeding of the actions of a public official by placing his conduct before an appropriate tribunal. In the American context, it is the presentation of formal charges against a public official by the lower US House of Representatives, followed by a trial before the upper house of the US Senate.

Washington presided when the Constitution was debated and written, inclusive of its provisions for presidential impeachment. A straightforward reading of the Constitution shows that Washington and the Framers embraced the provision for impeachment. They viewed it as a necessity for the preservation of republican government. To protect the integrity of the offices under the Constitution, they designed and ratified the process to remove incumbents unworthy to hold their positions.

Consider the specific Constitutional provisions that define how impeachment is to occur:

Article I, Section 2, Clause 5 says, “The House of Representatives shall choose their Speaker and other Officers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.”

Article I, Section 3, Clauses 6 and 7 state,

“The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two-thirds of the Members present.”

“Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.”

Article II Section 2 provides: “[The President] … shall have power to grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment”.

Article II, Section 4 declares, “The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

When the Framers thought of the Presidency and its powers as they penned the Constitution, they considered the sterling example of Washington. Yet being realists about human nature, they anticipated that America’s future could not expect an unbroken supply of leaders of his caliber. They consciously anticipated the likely sins of future fathers of national government and by necessity provided Congressional authority to remove powerful leaders from office for just cause. Washington praised the new Constitution and sought its ratification. He was without reservation in favor of its provisions for presidential impeachment.

That’s not to say that there were no concerns about the possibility that the power to impeach might itself be abused. While Washington did not directly address this, Alexander Hamilton did in Federalist Papers #65, writing under the penname, Publius. Hamilton was the first US Treasury Secretary and one of Washington’s closest confidants and penmen.

Publius warned of the difficulties that would result from impeachments as such efforts would inevitably be “POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.”

Hamilton then explained, “The prosecution of them, for this reason, will seldom fail to agitate the passions of the whole community, and to divide it into parties more or less friendly or inimical to the accused. In many cases it will connect itself with the pre-existing factions, and will enlist all their animosities, partialities, influence, and interest on one side or on the other; and in such cases there will always be the greatest danger that the decision will be regulated more by the comparative strength of parties, than by the real demonstrations of innocence or guilt.”

To put it simply, impeachment is always political. And the danger is always that the strength of parties (whether Democrat or Republican in our day) will have a greater impact than showing that the one being impeached is innocent or guilty. Hamilton understood human nature and his words have proven prescient when considered in light of presidential impeachments. Nevertheless, Hamilton favored the Constitution even with the risks attendant to the impeachment process since he viewed it as the best solution to an inevitable problem.

At this Presidents’ Day commemorating worthies such as Washington and Lincoln that nevertheless occurs in the context of a presidential Impeachment trial, how shall we celebrate?

First, be thankful to God for Washington’s wisdom, character and Constitution that blazed the trail for our nation. Second, remain grateful for the Constitution’s recognition of the imperfection of human nature by crafting effective means to preserve republican government and preserve it from human malfeasance. Third, pray that America will be blessed to celebrate many Presidents who serve with honor. Indeed, may they be far more than those, whether for cause or from political opposition, who will face Congressional fetters that impede their labors by means of the Framers’ provision for impeachment. Finally, let’s insist on a just result in this and all future impeachment trials—if the fetters don’t fit, then the Senate must acquit.