About Publications Library Archives

cthl.org

Preserving American Heritage & History

Preserving American Heritage & History

Summary

George Mason was a wealthy planter and an influential lawmaker who served as a member of the Fairfax County Court (1747–1752; 1764–1789), the Truro Parish vestry (1749–1785), the House of Burgesses (1758–1761), and the House of Delegates (1776–1780). In 1769, he helped organize a nonimportation movement to protest British imperial policies, and he later wrote the Fairfax Resolves (1774), challenging Parliament’s authority over the American colonies. In 1775, Mason was elected to the Fairfax County committees of public safety and correspondence. He represented Fairfax County in Virginia‘s third revolutionary convention (1775) and in the fifth convention (1776), where he drafted Virginia’s first state constitution and its Declaration of Rights, which is widely considered his greatest accomplishment. As a member of the House of Delegates, he advocated sound money policies and the separation of church and state. Mason represented Virginia at the Mount Vernon Conference (1785) on Potomac River navigation and at the federal Constitutional Convention (1787). Although Mason initially supported constitutional reform, he ultimately refused to sign the Constitution, and he led the Anti-Federalist bloc in the Virginia convention (1788) called to consider ratification of the Constitution. After Virginia approved it, Mason retired to his elegant home, Gunston Hall, on Dogue’s Neck, where he died in 1792.

George Mason the revolutionary was the fourth George Mason in Virginia. His great-grandfather came to America from England about 1660. By the time of Mason’s birth on December 11, 1725, at Dogue’s Neck, the Mason family had acquired substantial landholdings in Maryland and northern Virginia. Mason’s father drowned crossing the Potomac River in March 1735, and Mason, his oldest son, inherited the bulk of his estate.

In April 1750, Mason married Ann Eilbeck, the sixteen-year-old daughter of Colonel William Eilbeck, a prominent Maryland planter and merchant. They seemed to have enjoyed a happy marriage as suggested by what Mason wrote after her death: “in the Beauty of her Person, and the Sweetness of her Disposition, she was equaled by few, and excelled by none.” In 1754, the couple began the construction of a new home. Gunston Hall’s exterior and floor plan came from period building manuals, but Mason imported two gifted English artisans as indentured servants, carpenter and joiner William Buckland and woodcarver William Bernard Sears, to complete the interior work. Together they made Gunston Hall one of the finest homes in colonial America. By 1770, Ann Mason had given birth to ten children, nine of whom survived to adulthood. In December 1772, she delivered twin boys prematurely. It was a difficult pregnancy, neither boy lived, and she never regained her health. Her death in March 1773 sent Mason into a prolonged period of depression, although he continued to manage his varied business interests and to care for his large family. On April 11, 1780, Mason married Sarah Brent, the daughter of a family friend, George Brent. She was fifty, but it was her first marriage.

Despite the critical role Mason played in the American Revolution (1775–1783) and in the founding of the United States, he preferred life at Gunston Hall to public affairs, and he had interests beyond politics. An apparently conventional Episcopalian, he served for many years on the vestry of Truro Parish, whose members included his neighbor George Washington. An early advocate of religious freedom, Mason won passage in December 1776 of legislation repealing Virginia’s laws punishing heresy and requiring church attendance, and in November 1779, he persuaded the Virginia assembly to abolish the parish tax for clerical salaries.

As did many Virginia planters, Mason speculated in western lands. In June 1749, he became a partner in the Ohio Company, which held a royal grant for 200,000 acres at the forks of the Ohio River. Once the company built a fort and settled a hundred families in the area, it was to receive another 300,000 acres. In September 1749, Mason became the company’s treasurer and assumed most of the responsibility for its day-to-day operations. The Ohio Company’s forays into western territories claimed by the French probably helped provoke the French and Indian War in 1754, and the fighting made it impossible for the company to enforce its grant. Mason tried for years to obtain relief for the company from colonial and later American authorities but to no avail.

Mason had little formal education, but he seems to have read widely as a boy in the library of his uncle, the lawyer John Mercer. Blessed with a keen intellect, a forceful personality, and a sharp tongue, he quickly won the respect of his contemporaries. Philip Mazzei, an Italian doctor who visited Williamsburg in 1773, declared him a genius comparable to Dante, Machiavelli, Galileo, or Newton. Mason’s gifts made him a natural prospect for public office, which, more often than not, he tried to escape. After the death of his first wife, he attempted to avoid election to one of Virginia’s wartime conventions by citing “the duty I owe to a poor little helpless family of orphans to whom I now must act the part of father and mother both.” Public office, he said, would be “incompatible … with the daily attention they require.” Illness, real and perhaps imagined, provided another excuse, and chronic gout occasionally made it impossible for Mason to travel or work. Fundamentally, Mason disliked politics. He summarized his attitude in his will and advised his sons “to prefer the happiness of independence and a private station to the troubles and vexations of public business.” If, however, “their own inclination or the necessity of the times” led them into public service, they should never be deterred from “asserting the liberty of their country.”

Mason opposed the Stamp Act of 1765, which taxed most printed items in the American colonies, but he did not play a prominent role in the movement that led to its repeal. After the Townshend Duties levied new taxes on the colonies in 1767, Mason worked more actively with George Washington to develop a nonimportation plan to protest British policies. Although historians debate the extent of Mason’s contribution, he clearly wanted to ban the importation of slaves and British luxury goods. By 1774, when Parliament passed the so-called Intolerable Acts, which placed new restrictions on Massachusetts in the wake of the Boston Tea Party, Mason had become a leader of the patriot movement in Virginia. In July 1774, he drafted the Fairfax Resolves calling for the creation of a congress of all the colonies and for a renewed boycott of British goods. In August, a Virginia convention approved the resolves, and in October, a new Continental Congress adopted a Continental Association patterned after the Virginia resolutions.

Once the Revolutionary War began, Mason served in a third Virginia convention, and in the winter of 1775–1776, he worked as a member of the Fairfax County committees of safety and correspondence to outfit warships for the defense of northern Virginia and to procure supplies for troops in the area. Most important was his performance in the fifth Virginia convention during the summer of 1776. In May, the Continental Congress had asked each colony to prepare a constitution appropriate for an independent state. The following month, Mason took charge of a drafting committee and produced both a state constitution and a bill of rights. Collaborating mainly with Thomas Ludwell Lee, Mason wrote, as amended by the convention, a sixteen-part Declaration of Rights providing protection for freedom of religion, various safeguards for criminal defendants, and other fundamental liberties. As the first bill of rights appended to a written constitution, the Virginia declaration is widely considered the first modern bill of rights, and it became a model for similar documents, including the federal Bill of Rights. Thomas Jefferson would get much of the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence from the first article of Mason’s Declaration of Rights; it proclaimed “that all Men are born equally free and independent, and have certain inherent natural Rights, of which they can not by any Compact, deprive or divest their Posterity; among which are the Enjoyment of Life and Liberty, with the Means of acquiring and possessing Property, and pursueing [sic] and obtaining Happiness and Safety.”

If the Virginia Declaration of Rights stands as Mason’s greatest accomplishment, the Virginia constitution of 1776 suffered from many of the defects common to the first generation of state constitutions. Mason divided authority among executive, judicial, and legislative branches of government, but most power resided in a badly apportioned legislature that did not accurately represent the distribution of population between the East and West. A weak governor lacked veto power, the oligarchic county courts were left alone, and no provision was made for constitutional amendments. The convention rejected Mason’s proposal to expand voting rights beyond white male landowners. Despite its defects, however, voters accepted the new government, and Mason’s constitution remained in effect until 1830.

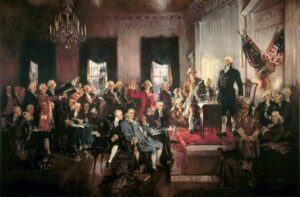

Mason made the longest trip of his life when he attended the federal Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1787. He recognized the need to replace the Articles of Confederation and to give Congress the power to levy taxes and to regulate foreign and interstate trade. He initially supported the Virginia Plan, which had been drafted by his fellow Virginian James Madison. Madison’s plan provided the basis for the convention’s deliberations. Mason participated enthusiastically, speaking, according to Madison’s notes, 136 times, among the most of all the delegates. Individual members brought different concerns to the convention. Mason feared a new Congress might adopt an American navigation law giving a monopoly to northern shippers. He wanted to ensure that southern planters had the ability to shop for the best rates for tobacco bound for European markets; at one point he persuaded the convention to require a two-thirds majority to adopt laws regulating foreign commerce.

The other delegates worried much more about the allocation of seats in Congress. A split between large and small states threatened to wreck the convention. Mason served on a committee that proposed a solution. In what came to be known as “the Great Compromise,” the committee proposed that seats in the United States House of Representatives be based on population, while each state would enjoy equal representation in the Senate. The convention approved the compromise over the opposition of a majority of the Virginia delegates, including Madison.

Another compromise, however, changed Mason’s attitude toward the emerging Constitution. New England and South Carolina delegates, he believed, reached an agreement to abandon the two-thirds requirement for trade regulations in exchange for a constitutional provision continuing the foreign slave trade until, at first, 1800, and, in the course of the debates, until 1808. The apparent deal appalled Mason. Although Mason owned dozens of slaves himself, he had repeatedly condemned the institution. He saw no easy way to abolish slavery where it was already well-entrenched but felt that few vested interests would be disturbed by ending the foreign slave trade. On August 31, Mason proclaimed he “would sooner chop off his right hand than put it to the Constitution as it now stands.”

Mason, nevertheless, continued to participate in the debates. On September 12, he offered to draft a bill of rights for the new Constitution. Some critics then and since have questioned his motives, suspecting he wanted to sabotage the convention by leading it into a legal morass. But Mason had long been devoted to protecting civil liberties, and his argument that the people would expect the Constitution to include a bill of rights proved prophetic. Any possibility that Mason would support the Constitution ended when the delegates, voting by state, decided unanimously to reject Mason’s offer.

Mason stayed in Philadelphia until the convention adjourned on September 17, but he refused to sign the Constitution. Before he left Philadelphia, he drafted a document titled “Objections to the Constitution,” explaining his position. He began with the complaint that “there is no Declaration of Rights.” The absence of a bill of rights became the strongest argument made by the Constitution’s Anti-Federalist opponents. The debate over the Constitution deeply divided Virginians. Mason’s Anti-Federalism was sufficiently unpopular in Fairfax County that he decided to run in Stafford County for a seat in the convention called to consider ratification of the Constitution. He won, and at the Richmond convention of 1788, he shared leadership of the Anti-Federalist forces with Patrick Henry. The convention voted 89 to 79 to approve the Constitution but also recommended that Congress consider numerous amendments. Mason doubted that Congress would approve meaningful revisions, and he largely retired from public life after the convention. He was, however, partially reconciled to the new government when James Madison shepherded a series of amendments through the first session of the new Congress, and Mason deserves credit for helping create the political momentum that led to the adoption of what became the federal Bill of Rights. He died at Gunston Hall on October 7, 1792.

Broadwater, J. (n.d.). Mason, George (1725–1792). Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/mason-george-1725-1792/.