About Publications Library Archives

cthl.org

Preserving American Heritage & History

Preserving American Heritage & History

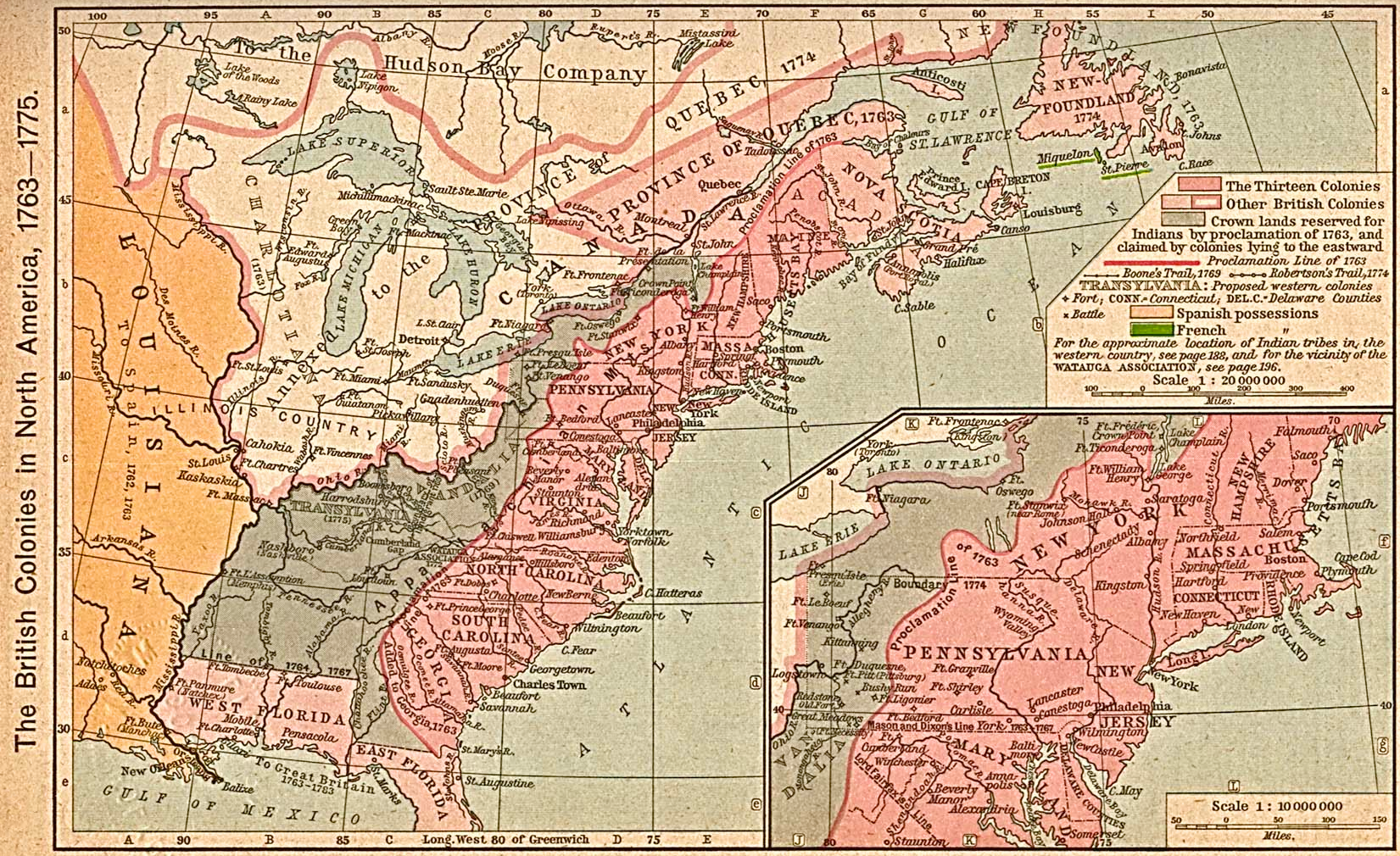

Henderson and frontiersmen thought the outbreak of the Revolution superseded the judgments of the royal governors. The Transylvania Company began recruiting settlers for the region they had “purchased”.

As tensions rose, the Loyalist John Stuart, British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, was besieged by a mob at his house in Charleston and had to flee for his life. His first stop was St. Augustine in East Florida. He sent his deputy, Alexander Cameron, and his brother Henry to Mobile to obtain short-term supplies and arms for the Cherokee. Dragging Canoe took a party of 80 warriors to provide security for the pack train. He met Henry Stuart and Cameron (whom he had adopted as a brother) at Mobile on 1 March 1776. He asked how he could help the British against their rebel subjects, and for help with the illegal settlers. The two men told him to wait for regular troops to arrive before taking any action.

When the two arrived at Chota, Henry Stuart sent out letters to the frontier settlers of the Washington District (Watauga and Nolichucky), Pendelton District (North-of-Holston), and Carter’s Valley (in modern Hawkins County). He informed them that they were illegally on Cherokee land and gave them 40 days to leave. People sympathetic to the Revolution forged a letter to indicate a large force of regular troops, plus Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Muscgoee, was on the march from Pensacola and planning to pick up reinforcements from the Cherokee. The forged letters alarmed the settlers, who began gathering together in closer, fortified groups, building stations (small forts), and otherwise preparing for an attack.

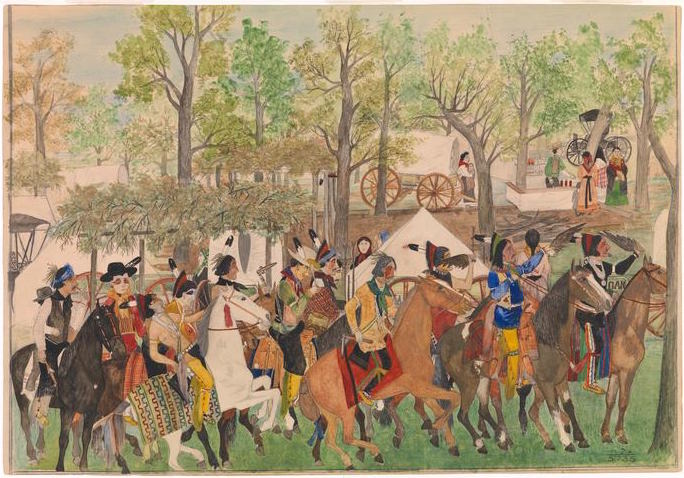

In May 1776, partly at the behest of Henry Hamilton, the British governor in Detroit, the Shawnee chief Cornstalk (Hokoleskwa) led a delegation from the northern tribes (Shawnee, Lenape, Iroquois, Ottawa, others) to the southern tribes. He traveled to Chota to meet with the southern tribes (Cherokee, Muscogee, Chickasaw, Choctaw) about fighting with the British against their common enemy. Cornstalk called for united action against those they called the “Long Knives“, the squatters who settled and remained in Kain-tuck-ee (Ganda-gi), or, as the settlers called it, Transylvania. At the close of his speech, Cornstalk offered his war belt, and Dragging Canoe accepted it, along with Abraham (Osiuta) of Chilhowee (Tsulawiyi). Dragging Canoe also accepted belts from the Ottawa and the Iroquois. Savanukah, the Raven of Chota, accepted the war belt from the Lenape. The northern emissaries offered war belts to Stuart and Cameron, but they declined to accept.

The plan was for the Cherokee of the Middle, Out, and Valley Towns, of what is now western North Carolina, to attack South Carolina. Cameron would lead warriors of the Lower Towns against Georgia. Warriors of the Overhill Towns, along the lower Little Tennessee and Hiwassee rivers, were to attack Virginia and North Carolina. In the Overhill campaign, Dragging Canoe was to lead a force against the Pendleton District, Abraham one against the Washington District, and Savanukah one against Carter’s Valley.

To prepare themselves for the coming campaign, the Cherokee began raiding into Kentucky, often with the Shawnee. Before the northern delegation had left, Dragging Canoe led a small war party into Kentucky and returned with four scalps to present to Cornstalk before they departed. In another raid, a war party led by Hanging Maw (Skwala-guta) of Coyatee (Kaietiyi), captured three teenage settler girls, Jemima Boone and Elizabeth and Frances Callaway, on 14 July, but lost them three days later to a rescue party led by Daniel Boone, father of Jemima, and Richard Callaway, father of Elizabeth and Frances.

In late June, war parties from the Lower Towns began attacking the frontier of South Carolina, and after the beginning July, the Out, Middle, and Valley Towns sent out war parties raiding the frontiers settlements of North Carolina east of the Blue Ridge.

Traders warned the squatters in Upper East Tennessee of the impending Cherokee attacks. They had come from Chota bearing word from Nancy Ward (Agigaue), the Beloved Woman (leader or Elder). The Cherokee offensive proved to be disastrous for the attackers, particularly those going up against the Holston settlements.

Finding Eaton’s Station deserted, Dragging Canoe took his force up the Great Indian Warpath, where he had a small skirmish with 20 militia. Pursuing them and intending to take Fort Lee at Long-Island-on-the-Holston, his force advanced. They encountered a larger force of militia six miles from Fort Lee. It was about half the size of his own but desperate and in a stronger position. During the “Battle of Island Flats” on 20 July, Dragging Canoe was wounded in his hip by a musket ball, and his brother Little Owl (Uku-usdi) was hit eleven times, but survived. His force withdrew, raiding isolated cabins on the way. After raiding further north into southwestern Virginia, his party returned to the Overhill area with plunder and scalps.

The next day, 21 July, Abraham of Chilhowee was unsuccessful in trying to take Fort Caswell on the Watauga, and his warriors suffered heavy casualties. Instead of withdrawing, he put the garrison under siege. After two weeks, he gave it up. Savanukah raided from the outskirts of Carter’s Valley deep into Virginia, but those targets contained only small settlements and isolated farmsteads, so he did no real military damage.

Despite his wounds, Dragging Canoe led his warriors to South Carolina to join Alexander Cameron and the Cherokee from the Lower Towns.

The colonials quickly gathered militia who retaliated against the Cherokee. North Carolina sent General Griffith Rutherford with 2400 militia to scour the Oconaluftee and Tuckasegee river valleys, and the headwaters of the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee. South Carolina sent 1800 men to the Savannah, and Georgia sent 200 to attack Cherokee settlements along the Chattahoochee and Tugaloo rivers. In all, they destroyed more than 50 towns, burned the houses and food stores, destroyed the orchards, slaughtered livestock, and killed hundreds of Cherokee. They sold captives into slavery, and these were often transported to the Caribbean.

Not long after leaving Fort McGahey on 23 July, Griffith Rutherford’s militia encountered an ambush by the Cherokee at Cowee Gap in what is now western North Carolina. After defeating the attackers, he proceeded to a designated rendezvous with the South Carolina militia.

On 1 August, Cameron and the Cherokee ambushed Andrew Williamson and his South Carolina militia force near the Lower Cherokee town of Isunigu known to whites as Seneca, in the “Battle of Twelve Mile Creek”. After retreating, he joined up with the militia force of Andrew Pickens.

The next day, 2 August, the joint militia force bivouacked, and Pickens led a party of twenty-five to forage for food and firewood. In what is known as the “Ring Fight”, two hundred Cherokee surrounded and attacked the party, which withdrew into a ring and were able to hold their attackers at bay until reinforcements arrived.

Pickens and his militia defeated the Cherokee on the Tugaloo River near the Cherokee town of the same name, which they then burned, on 10 August.

On 12 August, Williamson and Pickens defeated the Cherokee at the town of Tamassee. With this, they had completed their destruction of the Lower Towns, Keowee, Estatoe, Seneca, and the rest. Afterwards, they proceeded north to meet up with the North Carolina militia of Griffith Rutherford.

Rutherford’s militia traversed Swannanoa Gap in the Blue Ridge on 1 September, and reached the outskirts of the Out, Valley, and Middle Towns on 14 September, at which they started burning towns and crops.

Williamson’s militia were attacked at Black Hole near Franklin, North Carolina on 19 September, but were able to fend off the Cherokee and meet up with Rutherford to take part in the campaign of destruction.

In the meantime, the Continental Army sent Col. William Christian to the lower Little Tennessee Valley with a battalion of Continentals, five hundred Virginia militia, three hundred North Carolina militia, and three hundred rangers. By this time, Dragging Canoe and his warriors had already returned to the Overhill Towns.

Oconostota supported making peace with the colonists at any price. Dragging Canoe called for the women, children, and old to be sent below the Hiwassee and for the warriors to burn the towns, then ambush the Virginians at the French Broad River. Oconostota, Attakullakulla, and the older chiefs decided against that plan. Oconostota sent word to the approaching colonial army offering to exchange Dragging Canoe and Cameron if the Overhill Towns were spared.

Dragging Canoe spoke to the council of the Overhill Towns, denouncing the older leaders as rogues and “Virginians” for their willingness to cede land for an ephemeral safety. He concluded, “As for me, I have my young warriors about me. We will have our lands.” He stalked out of the council. Afterward, he and other militant leaders, including Ostenaco, gathered like-minded Cherokee from the Overhill, Valley, and Hill towns, and migrated to what is now the Chattanooga, Tennessee area. Cameron had already transferred there.

Upon reaching the Little Tennessee in late October, Christian’s Virginia force found Great Island, Citico (Sitiku), Toqua (Dakwayi), Tuskegee (Taskigi), Chilhowee, and Great Tellico virtually deserted. Only the older leaders remained. Christian limited the destruction in the Overhill Towns to the burning of the deserted towns.

The paramount mico Emistisquo led the Upper Muscogee in alliance with the British; within a year he had become the strongest native ally of Dragging Canoe and his faction of Cherokee. After 1777, he was assisted by Alexander McGillivray (Hoboi-Hili-Miko), the mixed-blood son of a Coushatta woman and a Scots-Irish American trader. He was mico of the Coushatta, a former colonel in the British Army, and one of John Stuart’s agents.

Although the majority of the Lower Muscogee chose to remain neutral, the Loyalist Capt. William McIntosh, another of Stuart’s agents and father of later Muscogee leader William McIntosh, recruited a sizable unit of Hitchiti warriors to fight on the British side.

Meanwhile, the Choctaw and the Chickasaw in alliance with the British patrolled the Mississippi and western Tennessee rivers to prevent American incursion along those pathways.

The Seminole of East Florida, universally Loyalist in sympathy, provided hundreds of warriors for British campaigns in the Southeast. They often fought with Loyalist Rangers commanded by Thomas Brown, formerly of Charlestown. Known to the whites as Cowkeeper, Ahaya, founder of the Seminole nation, was usually their leader.