About Publications Library Archives

cthl.org

Preserving American Heritage & History

Preserving American Heritage & History

The Coercive Acts of 1774, known as the Intolerable Acts in the American colonies, were a series of four laws passed by the British Parliament to punish the colony of Massachusetts Bay for the Boston Tea Party. The four acts were the Boston Port Act, the Massachusetts Government Act, the Administration of Justice Act, and the Quartering Act. The Quebec Act of 1774 is sometimes included as one of the Coercive Acts, although it was not related to the Boston Tea Party. These oppressive acts sparked strong colonial resistance, including the meeting of the First Continental Congress, which George Washington attended in September and October 1774.

The Boston Port Act was the first of the Coercive Acts. Parliament passed the bill on March 31, 1774, and King George III gave it royal assent on May 20th. The act authorized the Royal Navy to blockade Boston Harbor because “the commerce of his Majesty’s subjects cannot be safely carried on there.”1 The blockade commenced on June 1, 1774, effectively closing Boston’s port to commercial traffic. Additionally, it forbade any exports to foreign ports or provinces. The only imports allowed were provisions for the British Army and necessary goods, such as fuel and wheat. The Act mandated that the port remain shuttered until Bostonians made restitution to the East India Company (the owners of the destroyed tea), the king had determined that the colony was able to obey British laws, and that British goods once again could be traded in the harbor safely. However, if the Bostonians refused to pay the East India Company or the king remained unsatisfied, the harbor would be blockaded indefinitely.

The Massachusetts Government Act imperiled representative government in the colony. Assuming that Massachusetts was under mob rule, and to “[preserve] . . . the peace and good order of the said province,” Parliament passed the act on May 20, 1774. It received royal assent on the same day.2 The Massachusetts Council, previously constituted as an elected body with the governor’s approval, became appointed by the crown. Additionally, the Act gave the new royal governor the ability to choose judges and county sheriffs without the Council’s approval. County sheriffs could now also appoint jurors, harming the impartiality of the colony’s judicial system. The Government Act also restricted town meetings to once a year, with any additional meetings requiring the governor’s approval.

The Act for the Impartial Administration of Justice gained the king’s approval on the same day as the Massachusetts Government Act. This law sought to further increase the power of the governor by giving him the ability to move a trial to another colony or Great Britain if it was determined “that an indifferent trial cannot be had within the said province.”3 The Act eliminated the right to a fair trial by one’s peers, removing an established judicial principle dating to Magna Carta.

The Quartering Act was the fourth and final of the main Coercive Acts. It was given royal assent on June 2, 1774. The only act of the four to apply to all of the colonies, it allowed high-ranking military officials to demand better accommodations for troops and to refuse inconvenient locations for quarters. The inability to effectively house troops in North America had been a long-standing issue. Troops were often billeted far from the areas in which they operated, making it difficult for the army to exercise effective control over the colonists. However, the Act did not require colonists to house soldiers within their private homes, as is commonly believed. Rather, it specifically indicated that soldiers were to be housed in “uninhabited houses, out-houses, barns, or other buildings,” yet they were to be quartered at the colonists’ expense.4

The Quebec Act, sometimes included as one of the four Coercive Acts, was under consideration by Parliament before the Boston Tea Party. It became law soon after the legislation to punish Massachusetts was enacted. Also known as the Canada Act, the law extended the borders of the province of Quebec southward to the Ohio River. The Act also granted “the free Exercise of the Religion of the Church of Rome,” as the territory was home to a large French Catholic majority.5 While also instituting English criminal law, the act allowed French civil law to remain in place, which excluded trial by jury. The governor and legislative body established by the Quebec Act were crown-appointed positions with complete authority over the colony. At a time of widespread religious intolerance, many Protestant colonists shuddered at the prospect of tolerating Catholicism in North America.

The Coercive Acts were meant to break Massachusetts Bay and to warn the other colonies of the consequences of rebellious behavior. Each act was specifically designed to cause severe damage to a particular aspect of colonial life. The Boston Port Bill’s assault on colonial trade damaged the provincial economy, drove up unemployment, and starved the Boston people. The Government Act abolished representative government by establishing an all-powerful governor, and the Justice Act removed the right to a fair trial. The Quartering Act insured the close proximity of British troops to the colonists. Finally, the Quebec Act challenged some of the major reasons that colonists had fought in the French and Indian War—to defend and expand Protestantism and representative government in North America.

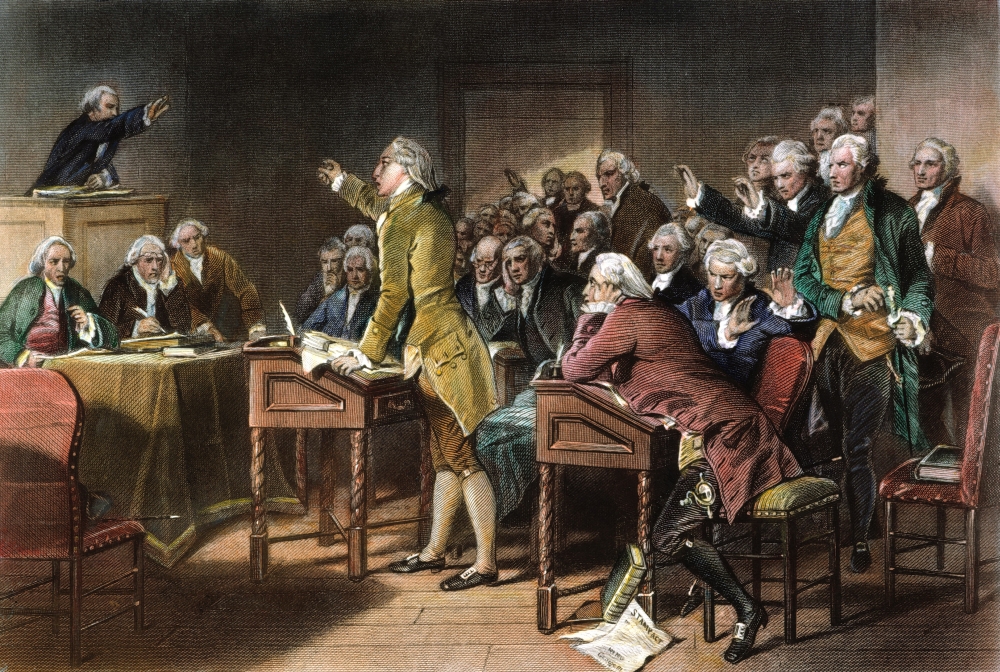

Understandably, colonists did not approve of the Coercive Acts. Yet, the petitioning of Parliament by individual colonies had already proved futile. On July 4, 1774, George Washington asked his friend Bryan Fairfax, “have we not addressed the Lords, and remonstrated to the Commons?”6 Thus, the First Continental Congress met on September 5, 1774, to coordinate a colonial response to Parliament’s actions. While attending the Congress, Washington advocated for what he called “the non-importation scheme,” or the boycott of British imports, which was similar to the Fairfax Resolves that he had earlier co-authored with George Mason.7 The Coercive Acts caused a clear shift in American public opinion. Where Washington had once questioned the radical Boston Tea Party, conceding “that we [do not] approve their conduct in destroying the Tea,” he now fully rallied behind the Bostonians, as he understood that the Coercive Acts threatened American liberty.8

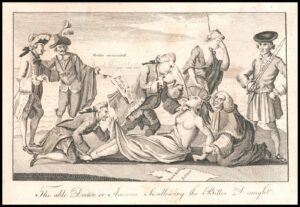

Parliament did not anticipate the colonies coming to Boston’s defense, and with good reason, as this was the first instance of mass colonial unification. Unlike previous controversial legislation, such as the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Townshend Acts of 1767, Parliament did not repeal the Coercive Acts. Hence, Parliament’s intolerable policies sowed the seeds of American rebellion and led to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in April 1775.

– The George Washington University

1. “The Boston Port Act: March 31, 1774.” Avalon Project – Great Britain: Parliament. Yale University, Lilian Goldman Law Library. Accessed October 29, 2018. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/boston_port_act.asp.

2. “The Massachusetts Government Act: May 20, 1774.” Avalon Project – Great Britain: Parliament. Yale University, Lilian Goldman Law Library. Accessed October 29, 2018. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/mass_gov_act.asp.

3. “The Administration of Justice Act: May 20, 1774.” Avalon Project – Great Britain: Parliament. Yale University, Lilian Goldman Law Library. Accessed October 29, 2018. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/admin_of_justice_act.asp.

4.”The Quartering Act: June 2, 1774.” Avalon Project – Great Britain: Parliament. Yale University, Lilian Goldman Law Library. Accessed October 29, 2018. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/quartering_act_1774.asp.

5. “The Quebec Act: October 7, 1774.” Avalon Project – Great Britain: Parliament. Yale University, Lilian Goldman Law Library. Accessed October 29, 2018. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/quebec_act_1774.asp.

6. George Washington to Bryan Fairfax, 4 July 1774, Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 13, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-10-02-0075.

7. Ibid.

8. George Washington to George William Fairfax, 10–15 June 1774, Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 13, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-10-02-0067.

Ammerman, David. In the Common Cause: American Response to the Coercive Acts of 1774. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974.

Beck, Derek W. Igniting the American Revolution: 1773-1775. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2016.

McCurdy, John Gilbert. Quarters: The Accommodation of the British Army and the Coming of the American Revolution. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2019.

Middlekauff, Robert. Washington’s Revolution: The Making of America’s First Leader. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2015.