About Publications Library Archives

cthl.org

Preserving American Heritage & History

Preserving American Heritage & History

NO SOONER had the news of the successful results achieved by Columbus reached Spain, than it spread like wild-fire through the then civilized world. The three other great maritime powers,—Portugal, England, and France,—were especially aroused to discover, if possible, lands for themselves. On the one side were Ferdinand and Isabella, who were determined to acquire and hold “the strange lands to the west,” whose possession had been guaranteed them by the Pope. On the other hand, there were the three other great powers, with whom desire of conquest and dominion existed no less strongly than with Spain. These nations were resolved to do all that lay in their power to acquire dominion; whatever difficulty might arise with Spain could be settled later.

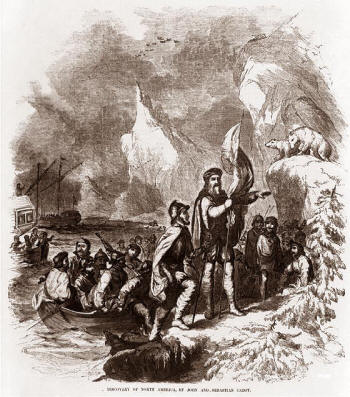

The first country to compete with Spain in western discovery was England, and the first one to follow in the footsteps of Columbus was John Cabot, who, with his son Sebastian, was destined to make important discoveries which would hand the name of Cabot down to history as surely as that of the great pioneer discoverer, Columbus, himself.

The first country to compete with Spain in western discovery was England, and the first one to follow in the footsteps of Columbus was John Cabot, who, with his son Sebastian, was destined to make important discoveries which would hand the name of Cabot down to history as surely as that of the great pioneer discoverer, Columbus, himself.

It was as early as 1492 that Senor Puebla, then the Spanish Ambassador to the Court of England, wrote to his Sovereigns that “a person had come, like Columbus, to propose to the King of England an enterprise like that of the Indies.” The Spanish King immediately instructed his minister that he should inform Henry VII that the prior claims of Spain and Portugal would be interfered with if he commissioned any such adventurer. But the warning came too late.

It is possible that the unsuccessful mission of Bartholomew Columbus to England, while the future Admiral was besieging the Spanish Court, may have been the means of arousing in John Cabot’s mind a desire to test the truth of the new theory of a westward path to the Indies. When the accomplished feat of the first voyage to the West Indies fired the imagination of Europe and became the chief topic of interest among the maritime nations, even cool-blooded England was measurably excited, and her parsimonious King yielded to the urgent prayers of a Genoese navigator, and authorized John Cabot and his three sons “to sail to the East, West, or North, with five ships, carrying the English flag, to seek and discover all the islands, countries, regions, or provinces of pagans in whatever part of the world.” We do not learn that this generous permission to sail and discover unknown countries was accompanied by anything more than a meagre provision for carrying it out, although the King in return for the commission given and the single vessel equipped was to have one-fifth of the profits of the voyage. According to at least one authority, Cabot had a little fleet of three or four vessels fitted out by private enterprise, ” wheryn dyvers merchaunts as well of London as Bristowe aventured goodes and sleight merchaundise wh departed from the West cuntrey in the begynnyng of somer—.” We are only sure, however, of one vessel, the Matthews, which left Bristol in May of 1497.

Choosing the most probable of several vague accounts of Cabot’s course in starting out, we find the sturdy adventurer, with his son and eighteen followers, standing to the northward, after leaving the Irish coast, and then westerly into the unknown sea. The plan was that which Columbus followed, when he sailed from the Island of Ferro in the Canaries, of striking a certain parallel of latitude and sticking to it. The transatlantic liners of today call that ” great-circle sailing.”

We have absolutely no record of the month or more spent upon the outward course. What strange experiences the Gulf Stream or the Labrador current presented to Cabot we can only surmise. There were no summer isles and turquoise seas for him. Instead of the song birds, the spicy breezes and silver sands that Columbus found, his less fortunate countryman came upon the forbidding coast of Labrador, bleak even in the summer time, where he saw no human beings.

It was on the 24th of June, 1497, that those on board of the Matthews unexpectedly caught sight of that strange, unknown land. They had no more notion than had Columbus of the magnitude of the discovery. This was to their appreciation no new world, but rather the extreme coast of the kingdom of the Grand Khan—a remote and desolate shore of India. But their imagination peopled it with strange beings; demons, griffins, and all the uncouth creatures of mediaeval mythology dwelt there with the bear and the walrus. If the South was the scene of brighter illusions, of kingdoms where the rulers lived in golden halls and fountains which could confer upon the bather the gift of perpetual youth, the glamour and legend which the cold crags of the North conjured up were not less characteristic. Haunted islands and capes, where the clamor of men’s voices were heard at night, were known to all the sailors and pilots that followed after the Cabots. The land that John Cabot first reached, wherever it was, he called “ Terra Firma.” There he planted the royal standard of England, after which he seems to have sailed southward; presumably to reverse the course by which he came over. Peter Martyr, in relating the wonders that Cabot discovered, recounts that “in the seas thereabouts he found so great multitudes of certain Bigge fishes much like unto Tunies (which the inhabitants called baccalaos) that they sometimes stayed his shippes.” Another writer stated that the “Beares also be as bold which will not spare at midday to take your fish before your face.” Coasting probably for three hundred leagues, with the land to starboard, Cabot seems to have discovered Newfoundland on the mainland side and to have passed through the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He named several islands and prominent points, but the names are uncertain and the localities problematical. We only know that in his opinion England would no longer have to go to Iceland for her fish, and that he relied upon his crew to corroborate his statements when he returned to England, because his unsupported word would not have established the fact of his discoveries. Royalty is not always liberal, despite the phrase “a royal giver”; for we learn right here of the munificence of the English King, who gave this intrepid sailor and discoverer ten pounds as a reward for his labor, and afterwards added a yearly pension of twenty pounds, or $100. There is something pathetic in this fragmentary story of the second continent-finder. The little spasm of approval and excitement which his success occasioned soon died away, and even at its height was utterly inadequate to the magnitude of his work. The simple sailor must have made as great a show as possible upon the stipend granted by the king, for we read in a letter of the Venetian, Pasqualigo, that “he is dressed in silk and the English run after him like a madman.”

Terra Firma.” There he planted the royal standard of England, after which he seems to have sailed southward; presumably to reverse the course by which he came over. Peter Martyr, in relating the wonders that Cabot discovered, recounts that “in the seas thereabouts he found so great multitudes of certain Bigge fishes much like unto Tunies (which the inhabitants called baccalaos) that they sometimes stayed his shippes.” Another writer stated that the “Beares also be as bold which will not spare at midday to take your fish before your face.” Coasting probably for three hundred leagues, with the land to starboard, Cabot seems to have discovered Newfoundland on the mainland side and to have passed through the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He named several islands and prominent points, but the names are uncertain and the localities problematical. We only know that in his opinion England would no longer have to go to Iceland for her fish, and that he relied upon his crew to corroborate his statements when he returned to England, because his unsupported word would not have established the fact of his discoveries. Royalty is not always liberal, despite the phrase “a royal giver”; for we learn right here of the munificence of the English King, who gave this intrepid sailor and discoverer ten pounds as a reward for his labor, and afterwards added a yearly pension of twenty pounds, or $100. There is something pathetic in this fragmentary story of the second continent-finder. The little spasm of approval and excitement which his success occasioned soon died away, and even at its height was utterly inadequate to the magnitude of his work. The simple sailor must have made as great a show as possible upon the stipend granted by the king, for we read in a letter of the Venetian, Pasqualigo, that “he is dressed in silk and the English run after him like a madman.”

A second voyage of John and Sebastian Cabot to discover the island of Cipango,—that illusory land that Columbus had so hopefully sought,—was undertaken; but a storm came up and one of the vessels was much damaged, finally seeking refuge in an Irish port. The others sailed into a fog of tradition and mystery as dense as that which wrapped the new-found land. We read that the expedition returned and that Sebastian Cabot lived to engage in further adventures, but of his father we know nothing further, the supposition being that he died upon this second expedition. Whether the third traditional voyage of Sebastian Cabot in the fifteenth century is fact or fable is not known. His subsequent career was mainly in the service of other sovereigns.

The profits of the second voyage of the Cabots were so meagre as to fail to arouse any enthusiasm; they were so small, in fact, that almost all interest died out in England. We read of one or two minor adventures, as those of Rut and Grube, the former of whom went to find the northern passage to Cathay, in which voyage his two ships encountered vast icebergs, by which one of them was lost and the other “durst go no further,” and after visiting Cape Race returned to England. With these few exceptions England took no part in the great work of discovery, by which, little by little, with here an island and there a headland, now a river and then a bit of coast, the results of that great discovery were combined into that which came to be known, though not at first, as the New World.

Yet Newfoundland was not deserted. Almost from the first the Breton and Basque fishermen, hardy and adventurous, frequented its shores. The Isle of Demons and other uncanny places in the new country were visited by fleets of French fishermen’s boats, and plenteous cargoes of “Baccalois,” or cod-fish, were taken eastward yearly for the Lenten market.

The year 1500 was one of extreme importance in the making of New World history. The Spanish and Portuguese had already settled their dispute over the division of territory, the Pope’s decision, to which all good Catholics in that day yielded unhesitating obedience, having given to Spain all land discovered west of a certain meridian line, and to Portugal whatever lay to the eastward. In this way Portugal acquired her right to the Brazils; and she also laid claim to Newfoundland. But the great element, time, had just begun to work. It was destined, under the ordering of Providence, that Spain and Portugal should make conquests, but not hold them. The Anglo-Saxon was only then a potentiality; his greatness was becoming recognized: he was yet to sweep the Atlantic, and, finally, settling on the stormy coast to the west, was to lay the foundations of a great empire, which was to make it possible to tell the inspiring and unique Story of America.

We now come to Americus Vespucius, who was, singularly enough, and through no scheming of his own, to give his name to a country that should rightly have borne the name Columbia. And he was to do this though he headed but one expedition. The story must necessarily be brief.

Vespucius was a Florentine—another conspicuous illustration of the fact that he was to discover even as Columbus had discovered, but Italy was to reap no benefit. He was, indeed, to sow the seed, but the strong arms of others were to reap the harvest. On the 9th day of March, 1451, Vespucius was born, in the city of Florence. Of a noble but not at all wealthy family, he received a liberal education, devoting himself to astronomy and cosmography. The fortunes of business took him to Seville, where he became the agent of the powerful Medici family. It was in 1490 that he became acquainted with Columbus, and was concerned in fitting out four caravels for voyages of discovery; he took an active part in assisting Columbus in preparing for his second voyage. Vespucius makes the statement, which we are prepared to accept, that in 1497 he sailed, and probably as astronomer, with one of the numerous expeditions that the success of Columbus had called into existence, leaving Cadiz on the 10th of May of that year. After twenty-seven days of sailing, the fleet, consisting of four vessels, reached a coast which we thought to be that of a continent,” traversing which they found themselves in “the finest harbor in the world.” Just what that harbor is it is impossible to say. Some writers have placed it as far south as Campeachy Bay; Chesapeake Bay has also been designated, Cape Charles being the point of entering. It is impossible, however, owing to Vespucius’s loose manner of writing, to fix the place with any certainty. But he states that he doubled Cape Sable, the southernmost point on the peninsula of Florida. Vespucius tells us that while in “the finest harbor” mentioned the natives were very friendly, and implored the aid of the whites in an expedition against a fierce race of cannibals who had invaded at different times their coasts, carrying away human victims whom they sacrificed by the score. The island in question was one of the Bahamas, one hundred leagues away. The fleet accordingly bore away, the Spaniards being piloted by seven friendly Indians. The Spaniards arrived off an island called Iti, and landed.

Here they encountered fierce cannibals, who fought bravely but unsuccessfully against firearms. More than two hundred prisoners were made captive, seven of them being presented to the seven Indian guides. But nearly a year had passed since they had left Cadiz. The vessels were leaky; it was time to return. Accordingly, leaving some point of the coast line of the United States, the fleet reached Cadiz on the 15th of October, 1498, with two hundred and twenty-two cannibal prisoners as slaves, where they were well received and sold their slaves for a good sum.

Still following Vespucius’s statement, on the 16th of May, 1499, he started on a second voyage in a fleet of three ships, under Alonzo de Ojeda. In this voyage Ojeda reached the coast of Brazil, and being compelled to turn to the north because of the strong equatorial current, they went as far as Cayenne, thence to Para, Maracaibo, and Cape de la Vela. They also touched at Saint Domingo. The expedition returned to Cadiz on the 8th of September, 1500. Three months later Yanez Pinzon, taking a like course, discovered the greatest river on the earth, the Amazon, as will be seen a little further on in this chapter. Ojeda just missed that discovery. A year later, for some reason dissatisfied with his position—and Vespucius seems to have passed at pleasure from one command to another—he entered the service of Emanuel, King of Portugal, and took part in an expedition to the coast of Brazil. He wrote a careful account of this voyage, which he addressed to some member of the Medici family, to whom, in 1504, he sent a fuller narrative of his expedition, which was published at Strasbourg. This gave him high reputation as a navigator and original discoverer.

Under the command of Coelho, a Portuguese navigator, on either May 10th or June 10th, 1503, a little squadron, with Vespucius, left the Tagus to discover, if possible, Malacca somewhere on the South American coast; but through mishap the fleet was separated, and Vespucius, with his own vessel, and later joined by another, proceeded to Bahia. Thence they sailed for Lisbon, arriving there, after about a year’s absence, on the 18th of June, 1504,

In a letter written from Lisbon, in 1504, to Rene, Duke of Lorraine, Vespucius gives an account of four voyages to the Indies, and says that the first expedition in which he took part sailed from Cadiz May 20, 1497, and returned in October, 1498. This letter has provoked endless discussions among historians as to the first discovery of the mainland of America, and it has been charged against Vespucius that after his return from his first voyage to Brazil he prepared a chart, giving his own name to that part of the country. It is high time the name of Vespucius was rid of this stain. It seems to be established that at this time the Duke Rene, of Lorraine, a scholar, and one deeply interested in the discoveries of the age, caused a map to be prepared for him by an energetic young student of geography, a young man named Waldsee-Muller, who innocently affixed the name America to the Brazil country. In this way the name became fixed, and was eventually taken up by others. It was not till nearly thirty years afterward—in 1535—that the charge of discrediting Columbus by affixing his own name was brought, and most unjustly so, against Vespucius. Latter-day opinion acquits Vespucius of this charge, and now with the fact established, at this time of our Columbian anniversary, it should no more be brought against the distinguished navigator, whose discoveries were important, if he did not accomplish all that was expected, and that through no fault of his. Vespucius died in Seville, February 2, 1512—six years after his predecessor, the first Admiral, had passed away.

The first man of importance to sail after Ojeda and Vespucci was Vincent Yenez Pinzon, who with his brother Ariez Pinzon, built four caravels, little deckless or half-decked yachts, with which he sailed from Palos in the month of December, 1499. Going further south than his predecessors, Pinzon bore away toward the coast of Brazil, his first land being discovered at a point eight degrees north of the equator, near where the town of Pernambuco was afterwards built: he was the first Spaniard to cross the equinoctial line. We read that he lost sight of the pole-star, a circumstance which must have alarmed his sailors. More wonderful still,—most miraculous it must have seemed,—was the finding of a great flood of fresh water, at the Equator, out of sight of land, which induced the navigator to seek for a very large river, and he found it!—for there was the mighty Amazon with its mouth a hundred miles wide and sending a great tide of fresh water a hundred miles out to sea. At their first landing Pinzon’s sailors cut the names of their ships and of their sovereign on the trees and the rocks, while he took possession of the land in behalf of Spain. Here Pinzon seized some thirty Indians as slaves. The mighty Amazon, with its hundred-mile wide mouth, filled the explorers with wonder, as well it might. But the capturing of the Indians had created difficulties which endangered the safety of the fleet, so that Pinzon deemed it prudent to shorten his stay. Accordingly he set sail, and skirting along the coast discovered the Orinoco River and Trinidad; after which they stood across to Hispaniola. A hurricane overtaking the little fleet nearly put an end to Pinzon’s adventure, but he finally escaped with the loss of two of his vessels. With the others he returned to Spain, only to find that Diego de Lepe had sailed after him and returned before him, with a report of the continuance of the South American continent far to the southward.

Rightly Da Gama has no place here, save as a discoverer in times of discovery. A skilled Portuguese mariner, he coasted the eastern shores of Africa and visited India. In a second voyage he became involved in hostilities with the towns of the Malabar coast. In 1499 he was made Admiral of the Indies. He died at Cochin, India, Christmas Day, 1524.

Rightly Da Gama has no place here, save as a discoverer in times of discovery. A skilled Portuguese mariner, he coasted the eastern shores of Africa and visited India. In a second voyage he became involved in hostilities with the towns of the Malabar coast. In 1499 he was made Admiral of the Indies. He died at Cochin, India, Christmas Day, 1524.

In 1499, the same year that the Pinzons and Lepe sailed, Pedro Alvarez de Cabral was commissioned by the Portuguese King, Emanuel, to follow Vasco da Gama’s course and establish a trading station on the Malabar coast. Gomez, for some reason unknown, sailed by the way of the Cape Verde Islands, and taking from thence a much more westerly course than he intended, came, quite by accident, upon the Continent that Pinzon and Lepe had so lately left. Probably the real cause of Cabral’s deflection from his original course was to avoid the calms of the Guinea shore. He had no sooner made the strange land than he resolved to cruise along it, and concluded that this wonderful coast was a continent. Dispatching a ship home to Portugal with the news— with Gaspar de Lemos in command—he pursued his voyage. When Pinzon returned, therefore, he not only found that Lepe had been there before, but ascertained that Portugal pressed its prior claim to the coast he had discovered, based on the Pope’s edict as well as the voyage of Cabral. The King of Portugal, on receiving Cabral’s message, soon despatched a fleet to discover new territory for his crown; and Americus Vespucius, till then in the Spanish service, accepted his overtures and went with the expedition. When Gaspar de Lemos started for Portugal with the news of the discovery of the southern continent, Cabral waited only a few days and then sailed southward.

The result of this second part of his voyage was the discovery of the Cape of Good Hope. There the fleet, heretofore so successful, was overtaken by a terrific storm, in the course of which four of his vessels went down, among them being one which was commanded by the navigator Bartholomew Diaz. The name which Cabral gave to this new country was Vera Cruz. The appellation by which it was afterwards known, of “Brazil” or “the Brazils,” was taken from the dye wood found there; an Arabic word being borrowed for the purpose. Columbus discovered the new world without knowing he had done so, although his work was in pursuance of carefully laid plans. Cabral however, like Vespucius off the North American coast, was aware from the first that the land he accidentally discovered was the mainland of a great continent.

After his adventure at the Cape of Good Hope Cabral went as far as Hindostan and returned with laden ships, in which were immense quantities of spices, jewels and rare merchandise. ” Verily,” said Vespucius, who met him in the Cape Verde Islands upon his return voyage, “God has prospered King Emanuel.” The same year [1500] that the Pinzons and Cabral sailed from their respective countries, Portugal sent the brothers Gaspar and Miguel Cortereal on the first of a series of new expeditions to explore the Northwest. The papal line of demarcation between Spanish and Portuguese possessions was called Borgia’s meridian, and the suspicion that Cabot’s discoveries lay to the eastward of this was sufficient cause for an expedition from Lisbon. These were unfortunate voyages, for although the region already explored by the Cabots was revisited and the flag of Portugal planted in the chill domain of the griffins and demons of Breton fancy, yet the wild men and curiosities which they brought home were but a sorry exchange for the lives that they cost. From Gaspar Cortereal’s second voyage he never returned. Two of his ships came home, and when his brother Miguel went in search of him his flag-ship also was lost, with all on board.

Rodigero de Bastidas and John de la Cosa, sailing with two ships from Cadiz, in 1502, discovered the Gulf of Darien, which point Ojeda on his second voyage also touched, thence proceeding to the West Indies. Following these, after a number of smaller adventurers that tried their fortune upon the Atlantic, Juan de Solis and Vincent Yanez Pinzon sailed from the Port of Saville, six years later. They directed their two caravels toward the coast of Brazil, going to the thirty-fifth degree south latitude, where they discovered the Rio de la Plata,—the River of Silver,—which they at first called Paranaguaza. To them also is due the credit for the discovery of Yucatan, on this same voyage. De Solis was by some considered the very ablest navigator of his time, and his fame at last induced the King of Spain to appoint him to the command of two ships fitted out to discover a passage to the Spice Islands, or Moluccas, for which he sailed in October, five years after he and Pinzon had made the trip just alluded to. He returned to the la Plata River, which stream he entered in January, 1516, but a tragic fate awaited him. Attempting to ascend the river and explore its banks, de Solis and a number of his crew were surprised and overpowered by the natives, who roasted and ate the unfortunate Spaniards in the sight of their companions on the vessels. The survivors, sickened and terrified by such a. spectacle, lost no time in escaping from the land of these cannibals. They stopped only at Cape San Augustin, where they loaded their vessels with Brazil wood, and made the best of their way back to Europe with the sad news. In the following year Charles V sent Cordova, with a command of 110 men in three caravels, into that distant but no longer dreaded West, which still had its rewards for the adventurer.

Upon the shore of Yucatan, where he first landed, at Cape Catoche, the Spaniards saw with surprise people who in one respect differed very greatly from the natives who had so far been met with in the western voyages, inasmuch as they dressed in cotton and other fabrics, instead of going naked and painting their bodies. Not only in their dress but in their houses they exhibited signs of civilization that excited the wonder of Cordova and his men.

Six years had passed after the death of Columbus, when, in 1512, Juan Ponce de Leon sailed from Puerto Rico in a northerly direction and discovered the peninsula which the Admiral had so nearly found upon his first voyage. De Leon first sighted land at about the boundary line separating Florida from Georgia. Landing, he took possession in the name of his sovereign, calling the new country Florida; for it was in April, when the Cherokee roses, the wild jessamine, and all the multitudinous blossoms of a Floridian spring-time were filling the air with their fragrance. The discoverer of this paradise returned to Spain, and, obtaining the governorship of the new coast, undertook to enter upon its possession. But the natives were otherwise minded. The followers of Ponce de Leon were hunted through the tangled growth of the luxuriant forests or harassed in their defenses behind the sand-dunes, till many of them had been killed, and their leader was glad to escape with the little remnant of his force. So he re-embarked, abandoning the country; but the Spaniards claimed Florida from that day, in spite of a counter-claim which England presented in virtue of the discoveries of the Cabots. Later, in 1527, Pamphilo de Narvaes repeated Ponce de Leon’s experiment, with a similar result. Then Ferdinand de Soto, who had been Governor of Cuba, obtained the title of Marquis of Florida, and, with nearly a thousand men and ten ships, he landed, in 1539, on the west coast of the peninsula. Five years later a little handful of broken, impoverished, beaten, disheartened Spaniards, less than a third of the number that had sailed so proudly to the conquest of Florida, left its shores to the sole occupancy of the jealous natives who inhabited it. There was no perpetual “fountain of youth ” there for de Soto, but ageing, weariness, and disaster instead.

Six years had passed after the death of Columbus, when, in 1512, Juan Ponce de Leon sailed from Puerto Rico in a northerly direction and discovered the peninsula which the Admiral had so nearly found upon his first voyage. De Leon first sighted land at about the boundary line separating Florida from Georgia. Landing, he took possession in the name of his sovereign, calling the new country Florida; for it was in April, when the Cherokee roses, the wild jessamine, and all the multitudinous blossoms of a Floridian spring-time were filling the air with their fragrance. The discoverer of this paradise returned to Spain, and, obtaining the governorship of the new coast, undertook to enter upon its possession. But the natives were otherwise minded. The followers of Ponce de Leon were hunted through the tangled growth of the luxuriant forests or harassed in their defenses behind the sand-dunes, till many of them had been killed, and their leader was glad to escape with the little remnant of his force. So he re-embarked, abandoning the country; but the Spaniards claimed Florida from that day, in spite of a counter-claim which England presented in virtue of the discoveries of the Cabots. Later, in 1527, Pamphilo de Narvaes repeated Ponce de Leon’s experiment, with a similar result. Then Ferdinand de Soto, who had been Governor of Cuba, obtained the title of Marquis of Florida, and, with nearly a thousand men and ten ships, he landed, in 1539, on the west coast of the peninsula. Five years later a little handful of broken, impoverished, beaten, disheartened Spaniards, less than a third of the number that had sailed so proudly to the conquest of Florida, left its shores to the sole occupancy of the jealous natives who inhabited it. There was no perpetual “fountain of youth ” there for de Soto, but ageing, weariness, and disaster instead.

When Charles V, of Spain, was beginning to feel the benefit of the conquest in the New World, and Cortez and the Spanish captains and adventurers were planting the standard of Spain in rich territory, Francis the First, of France, chafed at the necessity of acknowledging the success of his rival. Francis was one of the most curious characters of European history, a combination of good and evil traits. Vanity, culture, sensibility to the influences of art and literature, hatred, malice, and all uncharitableness distinguished him. He was the friend of philosophers and of those who were far from being philosophers.

When Charles V, of Spain, was beginning to feel the benefit of the conquest in the New World, and Cortez and the Spanish captains and adventurers were planting the standard of Spain in rich territory, Francis the First, of France, chafed at the necessity of acknowledging the success of his rival. Francis was one of the most curious characters of European history, a combination of good and evil traits. Vanity, culture, sensibility to the influences of art and literature, hatred, malice, and all uncharitableness distinguished him. He was the friend of philosophers and of those who were far from being philosophers.

From Florence came Verazzano, a navigator of repute who, unlike most of the new world-finders, was by birth a gentleman, descended from men who had been prominent in Florentine history. He was appointed to sail westward from Dieppe with four ships, in the year 1523, to seek a new passage to that Cathay which still lured the hopes of Christendom; and in passing we may remark upon the curious irony of fortune which permitted Italy to lend to other nations the men who should win the greenest laurels as discoverers, when she herself was unable to claim a foot of territory in the new world. The beginning of Verazzano’s voyage was puzzling enough. He had not proceeded far from Dieppe when a storm overtook him and he escaped with two of his vessels to Brittany; thence he cruised against the Spaniards and finally, having but one vessel left out of the four with which he started, he set sail for the island of Madeira, and on the 17th of January, 1524, turned the prow of his caravel, the Dolphin, westward, to cross the Atlantic. After a passage of forty-five days, during which the strange experiences common to such an adventure were not lacking, he sighted a low shore where vast forests of pine and cypress rose from the sandy soil. This was not far from the present site of Wilmington, North Carolina. Among other things the Florentine noticed the presence of many fragrant plants “which yeeld most sweete savours farr from the shore.” The natives who appeared on shore attracted the greatest attention from the voyagers since they were not at all sure what their reception might be when they landed for the supply of water of which they stood in need. A boat approached as near as possible to the beach, when one of the sailors, taking some gifts as a propitiatory offering, jumped overboard and swam through the surf. But as he neared the beach and saw the throng of screeching red men who awaited him his courage failed, and flinging his presents among them he endeavored to return; but the men succeeded in capturing him and returned to the sand, where in the sight of the terrified captive they built a great fire. Instead, however, of cooking him, as he expected, they warmed and dried him, showed him every mark of affection, and then led him to the shore and let him go. At the next place they touched, the crew of the Dolphin showed their appreciation of the courtesy of the Indians by stealing one of their children.

From the Carolinas Verazzano’s course was northward along the coast, his first anchorage being in the bay of New York. Into that beautiful harbor, through the Narrows and under the green and tree-covered banks of Staten Island, he rowed, being met by numerous canoes filled with Indians who came out to welcome him. From New York the Dolphin followed the Long Island coast as far as Block Island, and from there to the harbor of Newport, where for fifteen days they rested, being entertained by two chiefs, who did all that lay in their power to dazzle the eyes of their white visitors with the signs of opulence, as evidenced by copper bracelets, wampum belts, the skins of wild beasts, etc.

From here the little vessel steered along the New England coast, neither officers nor seamen finding much to attract them. The Indians were suspicious and inhospitable, driving them back with shouts and showers of arrows when they ventured ashore in their boats. The seaboard of Maine was visited, and then the banks of Newfoundland, from which last point Verazzano, whose expedition was for us, perhaps, the most significant of all, sailed back for France, having explored the American coast from Hatteras to Newfoundland.

In the following year Verazzano sailed again from France with a fleet, but no news of that expedition ever came back, and the mystery of its loss chilled the ardor for discovery in that country, so that for several years we hear of no further adventures to the new world. But in 1534 the persuasions of Admiral Chabot led to the issuing of a commission to Jacques Cartier, of St. Malo, who sailed from that port in the same year with two ships and one hundred and twenty-two men. He circumnavigated Newfoundland and explored the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and upon a second voyage sailed up the river of the same name for three hundred leagues, as far as the “great and swift Fall.” On the site of Montreal he visited an Indian town. Having attempted the settlement for which he had been sent out, Cartier went back to France only to return with a larger expedition to Canada five years later.

Half a century of discovery and adventure had elapsed. The map-makers of Europe during that time were kept busy by the changes made necessary from fresh data requiring the readjustment of old lines. From Columbus to Verazzano and Cartier, the whole coast, with a few exceptions, had been discovered, from the stony crags of Labrador to the Cape of Good Hope. It only remained now for the round-up of this magnificent hunt, which was accomplished by the intrepid Magellan, prince of navigators, who, first turning westwardly across the Pacific found the true path to far-off Cathay, which the mighty Genoese had sought so patiently, so grandly, so mistakenly, among the isles of June and the pearl banks of the Caribbean Sea.

More than ordinary romance and interest attend the story of Vasco Nunez de Balboa. His appearance in the story of Spanish conquest in America, if not dignified, is captivating to the imagination. Martin Fernandez de Enciso, the geographer, sailed from St. Domingo to go to the relief of the explorer, Ojeda, who was dying of famine at San Sebastian. Among the stores in his vessel was a cask which contained something more valuable than the bread which it was invoiced as containing. When Enciso’s ships had got fairly out to sea, Balboa crept out of his cask and presented himself to the commander, who could, after all, do nothing but scold, as it was then too late to return the fugitive to the creditors from whom he had taken that means of escaping. There were some threats of putting the culprit ashore on a small desert island, but that was not done, or one of the most popular stories of the New World would have been unwritten but by the time the expedition in search of Ojeda had been abandoned and the followers of Enciso, reinforced by the haggard remnant of Ojeda’s force, had reached the Gulf of Uraba, Balboa was no inconsiderable figure in that company.

When the building of Santa Maria del Darien had commenced and Enciso’s temper provoked an insurrection, the stowaway, Balboa, was spoken of as his successor. The newcomers had encroached on the province of Nicuesa, who had been given a province in Darien, of which he was Governor, at the same time that Ojeda was similarly favored by King Ferdinand. Some of them, therefore, were for giving their allegiance to that Governor. The matter was settled by giving Balboa charge till Nicuesa should come.

Nicuesa, embittered by famine and all manner of hardship, was rejected by the men of Darien when he finally came to them, and, turning his poor little brigantine seaward, was never heard from again. The cruelty shown to him at this time was afterward charged upon Balboa, but he was cleared by the court. He, however, showed little kindness to the irate Enciso, who went home to Spain an avowed enemy, complaining bitterly of the treatment he had received at the hands of the stowaway, whom, doubtless, he regretted not having “marooned,” i.e., cast on a desert island, when he had the chance.

Balboa next explored Darien. He married a native princess, thus making the old chief Comogre, her father, his firm friend. The first evidence which the Spaniards had of the superior claims of the people of Central America to civilization was at Comogre’s house, where “finely wrought floors and ceilings,” a chapel occupied by ancestral mummies, and other signs of ease and leisure, appeared. But dearer than anything else was the sight of ornaments and flakes of virgin gold. This the Spaniards, with their usual propensity, acquired, and marveled at the strange tales which were told them of a land further to the west-ward where the people made bowls and cups of the yellow metal. This was the first news they had received of the kingdom of Peru. Balboa sent the whole of the story and a fifth of the gold to Spain as Ferdinand’s share, but the ship went down on the voyage. Its arrival at Court would have done more than anything else to check the legal proceedings which were being commenced against him at home. However, Balboa was appointed Captain-General of Darien, by the Government of Hispaniola, which was some little comfort to him.

Balboa next advanced across the Isthmus to find the “great sea” of which he had heard. On the twenty-fifth of September, in 1513, after some trouble with the Indians, Vasco Nunez de Balboa stood where the poet Keats has made Cortez stand for some years past, on a peak in Darien, a mountain in the country of Quarequa, and looked with the glad eyes of a discoverer on the blue waters of the mighty Pacific Ocean, that till then had had no herald in the Eastern world. Having shortly after this gained the Pacific coast, Balboa returned to Darien with the news of his great discovery, which might have gained him the gratitude and reward it merited had not Pedrarias Davila succeeded in gaining the royal ear, and with a band of cavaliers, lured to new fields by the golden rumors of Peru, started for Darien. By his commission Davila was Admiral and Governor; he was a leading figure on the Isthmus for sixteen years, and during that time committed so many crimes that the historian Oviedo computes that he would have to face two million souls at the judgment day! Oviedo, like the humane Las Casas, believed that the Indians possessed souls; and though we know how given the Spanish chroniclers were to exaggeration and even downright mendacity, still we cannot doubt that enough murders were committed during the governorship of Davila to make even the conscience of a Spaniard feel uncomfortable. With the cavaliers who came over with Davila were Oviedo, the historian already named, and Enciso, Balboa’s old commander. The first thing that the jealous Davila did was to arrest Balboa on trumped-up charges, but they did not suffice to insure his conviction, and about this time the news of his great discoveries was beginning to turn the tide in Spain in his favor. It is to be said to Balboa’s credit that he was very politic in his treatment of the Indians, using kindness where the new Governor practiced the utmost cruelty. As a result Balboa was regarded with friendly feelings and his rival hated,—a condition of affairs that could not fail to engender jealousy and danger.

The Spanish bishop, who had come with the expedition, strove to patch up matters by suggesting a betrothal between Balboa and the daughter of the Governor. As the daughter was in Spain, and the alliance could not be consummated for some time, Balboa consented, though we have no evidence that he really contemplated abandoning his beloved Indian wife. The proposed marriage was but one article in an important treaty, without which the younger man would have been crushed by the elder.

Before long, however, Balboa again incurred the hatred of his enemy, and accepting a treacherous invitation- to visit him, was arrested by his old comrade, Pizarro, and beheaded, at the age of forty-two, in the land with which his name and fame are indissolubly connected. It was just before his last quarrel with Davila, which resulted in his untimely end, that Balboa performed one of the most astonishing feats in Spanish-American annals: having taken his ships apart he transported them across the Sierras, and launched them on the Pacific.

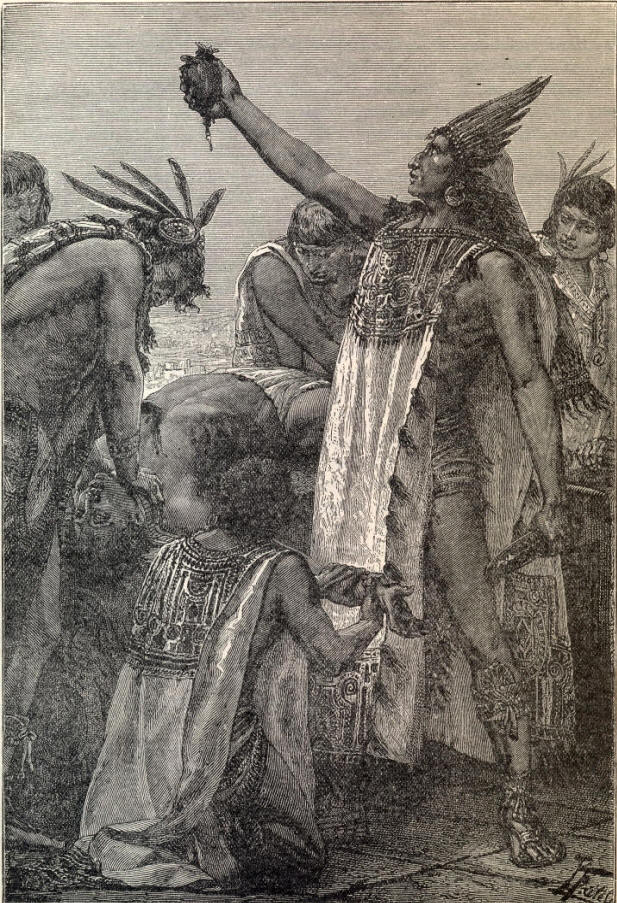

Ferdinand de Soto was born in Xeres, Spain, in 1500. We first meet with him, so far as American exploration is concerned, on accompanying his friend and patron Davila [previously referred to in the account of Balboa], on his expedition to Darien, of which Davila was governor, and whose offensive administration De Soto was the first to resist. He supported Hernandez in Nicaragua in 1527, who perished by the hand of Davila for not obeying his instructions. Withdrawing from the service of Davila, in 1528 he explored the coasts of Guatemala and Yucatan for 700 miles, in search of the strait which was supposed to connect the two oceans. In 1532, by special request of Pizarro, he joined him in his enterprise of conquering Peru. He was present at the seizure of the Peruvian Inca, and took part in the massacre which followed, serving the usual apprenticeship in butchery which hardened the hearts and made callous the nerves of those who followed the Spanish conquerors: but we are told he condemned the murder of the Inca Alahualpa, as well he might!

In 1537, De Soto was appointed Governor of Cuba , and two years later he crossed the Gulf of Mexico to attempt the conquest of Florida at his own expense, believing it to be the richest province yet discovered. Anchoring in Tampa Bay, May 25th, 1539, his route was through a country made hostile by the violence of the Spanish invader, Navarez.  It was fighting all the time, but it was not conquest. He continued to march northward, reaching, October 18th, 1540, the present site of Mobile, Alabama, and finally arriving at the mouth of the Savannah river. That country was then, as it is now, flat and sandy, its low forests of pine interspersed with cypress swamps and knolls where the live-oaks flourished. Frequent streams intersect portions of it. Traveling with such means as De Soto had at his disposal was very slow and trouble-some. From the Savannah he turned inland, fighting the Indians at almost every step, and overcoming mighty obstacles. With nearly a third of his men slain or lost, after a winter spent on the Yazoo, and disappointment following disappointment as he searched in vain, in his westward course, for the cities of gold which he saw in glowing but illusory vision, after a year and a half of unparalleled hardships and constant marching, in April, 1542, he discovered the Mississippi, that mighty stream whose current flows for four thousand miles, upon which the eyes of a white man had never before rested. This he explored for a short distance above and below Chickasaw Bluffs. Here his great career ended, for he died of malignant fever. To conceal his death from the Indians, his body was wrapped in a mantle, and in the stillness of midnight was silently sunk in the middle of the stream. His soldiers pronounced his eulogy by grieving for their loss, while the priests chanted the first requiem ever heard on the waters of the Mississippi.

It was fighting all the time, but it was not conquest. He continued to march northward, reaching, October 18th, 1540, the present site of Mobile, Alabama, and finally arriving at the mouth of the Savannah river. That country was then, as it is now, flat and sandy, its low forests of pine interspersed with cypress swamps and knolls where the live-oaks flourished. Frequent streams intersect portions of it. Traveling with such means as De Soto had at his disposal was very slow and trouble-some. From the Savannah he turned inland, fighting the Indians at almost every step, and overcoming mighty obstacles. With nearly a third of his men slain or lost, after a winter spent on the Yazoo, and disappointment following disappointment as he searched in vain, in his westward course, for the cities of gold which he saw in glowing but illusory vision, after a year and a half of unparalleled hardships and constant marching, in April, 1542, he discovered the Mississippi, that mighty stream whose current flows for four thousand miles, upon which the eyes of a white man had never before rested. This he explored for a short distance above and below Chickasaw Bluffs. Here his great career ended, for he died of malignant fever. To conceal his death from the Indians, his body was wrapped in a mantle, and in the stillness of midnight was silently sunk in the middle of the stream. His soldiers pronounced his eulogy by grieving for their loss, while the priests chanted the first requiem ever heard on the waters of the Mississippi.